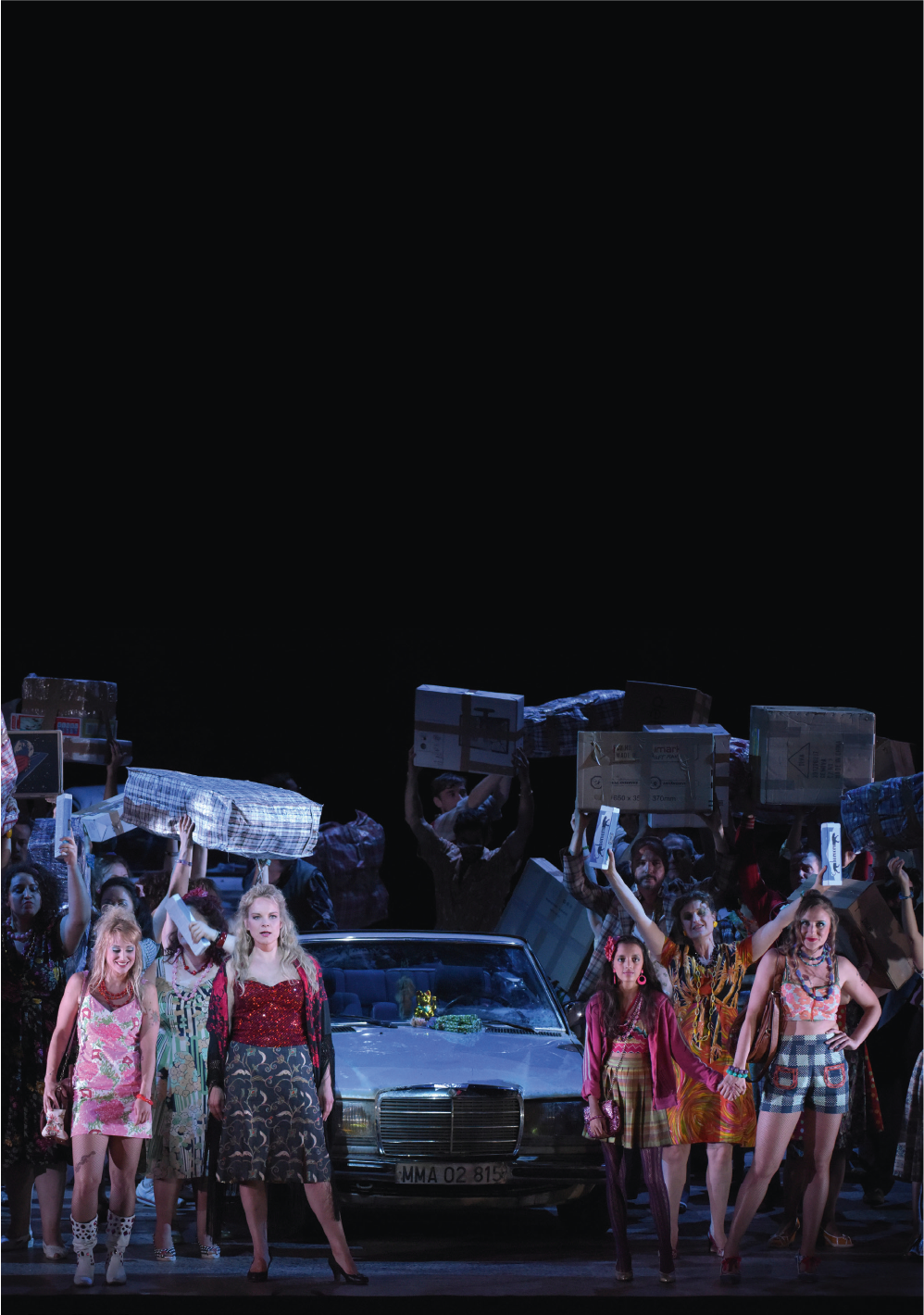

Massenet's Cinderella enters the Paris National Opera repertoire, and raises the eternal question: why offer today's audience a new reading of a classic tale? An essential question, however, because it is proof that these stories, however old they may be, still have a lot to tell us.

Cinderella was published in 1697 in the Histoires ou contes du temps passé aves des moralités, a volume of prose tales with a dedication 'To Mademoiselle', otherwise known as Elisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans, niece of Louis XIV. The frontispiece illustration, opposite the title page, depicts three characters seated in front of the hearth, facing an elderly spinner; above them is a sign bearing the words: "Contes de ma mère l'Oye". This inscription accompanies a scene of storytelling and is immediately suggestive of folklore, which seems to be confirmed by the absence of an author's name on the title page. The dedicatory epistle, on the other hand, is signed by a certain "P. Darmancour", who introduces himself as "a Child": this is Pierre Perrault, known as Perrault Darmancour, son of Charles Perrault and nineteen years old in 1697. This editorial stratagem, which has been commented on extensively by generations of critics, allows Charles Perrault to make people believe in the relative simplicity of the stories that follow - since they were written by "a Child" - even though the epistle implies multiple readings when it evokes "a very sound Morality, [...] which is perceived more or less, according to the degree of penetration of those who read them".

In the context of the quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns, these tales were also a way for Perrault to compete with La Fontaine, whose third volume of Fables was published in 1694, while his own Contes et nouvelles (1665-1671) were criticised for their lack of morality. Perrault therefore contrasted his Contes, "bagatelles" intended to "instruct", with the voluntarily saucy tales of the famous fabulist, without placing himself under the authority of an author from Antiquity.

In 1899, there were two French translations of the Grimm brothers' version, that of Frank and Alsleben (1869) and that of Charles Deulin (1878), but it was on Perrault's text, which was better known to the French public and less cruel, that Henri Cain, Massenet's librettist, based his work. He gives real substance to Cinderella's father, whom he names Pandolfe, a father whom Perrault only mentions at the opening of the tale, and then does not bother with at all. Cain takes advantage of this to redistribute the roles, thus departing from the source tale. This is one of the major changes: the father whom, in Perrault, "his wife [...] governed entirely", is just as submissive in Massenet's opera, but at least he is aware of this, describing himself in the second scene of Act I as "husband, twice-husband, very married", and full of compassion for his daughter, Lucette, with whom he shares long and tender scenes (Act III, scene 3; Act IV, scene 1). Massenet thus rebalances, through his librettist, the relationships between the characters by reintroducing the father figure, thus softening the fate of Cinderella. The stepsisters, on the other hand, are nothing but superficial and foolish, equally subject to a tyrannical and calculating mother who is determined that her offspring should not only make a good impression, but also be victorious at the ball, which is compared to a 'battlefield'.

Massenet remains very faithful to the plot of Cinderella, while adapting it to the means of expression specific to opera. While Perrault's text, faithful to the fairy-tale genre, externalizes the cruelty of the stepmother and her daughters, in Massenet and Cain's work Cinderella is not seen "cleaning the dishes and the stairs", nor carrying out the other chores that punctuate her daily life. During the preparations for the ball, Mme de La Haltière brings in milliners and hairdressers, which mitigates Cinderella's humiliation by her sisters. Only Lucette's long complaint (Act I, scene 5), 'Stay at home, little cricket [...]', and Pandolfe's reproaches, give us a sense of the young girl's resigned suffering.

Faced with the heroine's misfortune, the action of the tale follows a logic of reparation and compensation, playing on contrasts: the greater the distress, the more complete the final triumph. Ashes and rags are contrasted with a dress made of the rays of the stars and the thousand lights of the ball. The marvellous, embodied in Perrault by the Fairy Godmother alone who changes the pumpkin into a carriage, the mice and lizards into horses and lackeys, is transferred in Massenet to the marvellous dress, made of "joyful rays" stolen from the "radiant stars" (Act I, scene 6), and multiplied thanks to the spirits and the will-o'-the-wisps, to which are added the movement of birds and insects, and the twinkling of fireflies. The consoling and restorative function of the tale, and its playful function, through the wonder that it provides, come together here, and we all know the major role played by the lighting during the creation of this opera in 1899.

The "Electricity Fairy" has lost its power to amaze, so much so that it is part of our daily lives, but the tale of Cinderella told by Massenet and Henri Cain continues to bring comfort and hope. The poor orphan girl finds happiness in the prince but rescuing her from her miserable condition is not his only merit. Much more than the good fortune he represents, it is the meeting of two beings, of two souls, that is at the heart of the story.

The genre of the tale has been constantly updated and reread in the light of the questions or debates specific to a given era and society. Recently, there has been some concern about whether the vision of women conveyed by fairy tales is not old-fashioned, macho and therefore harmful, among other things because of a kiss straight out of Walt Disney's imagination. This is to forget, under the effect of the #MeToo movement, that the tales as well as their rewritings are each anchored in an era, in eras not all of whose values are still relevant. Exactly, not all. Because if the fairy-tale is so present on screens, on theatre and opera stages, from the most confidential to the most prestigious, it is because it still speaks to us today.

The tale lives on and the marvellous evolves, according to the period and its audience. Cinderella, like other tales, has been reused and transposed in many ways, in all media, even including a famous rock version. The magic of technical prowess has faded with the widespread use of special effects, and it is finally to the essential that the tale, an optimistic genre par excellence, brings us back. The motif of the slipper, which is only suitable for one girl, expresses, in the symbolic language of the tale, the profound and unbelievable affinity that lies in the loving encounter of two beings. Whether this magic works on everyone, including the stepmother, is open to doubt, but after all, isn't believing in this harmonious outcome part of the pact that the tale makes with its audience? Reality is suspended, the everyday is reenchanted as long as the tale lasts, which is particularly necessary today.