It is Donizetti and, through him, that charlatan Dulcamara who were right: love potions do exist! And when an ethno-psychiatrist as charming as Tobie Nathan affirms it, there is every reason to believe him.

I’d like to begin this interview with a paradox that intrigues me: you pursue a highly serious vocation – that of ethno-psychiatrist – and yet you have entitled your book Philtre d'amour. Comment le rendre amoureux? Comment la rendre amoureuse? (Love philtres. How do you make someone fall in love?)

Tobie Nathan: For centuries people have believed that love grew naturally between two beings mutually charmed by their harmonious bodies, pretty faces or noble souls. The idea of the love potion, which is the starting point of both Donizetti’s opera and my research, suggests the opposite: that desire can only be aroused by a deliberate act. Mind you, I’m referring here not so much to love as to passion. In Greek there are two words to denote love: Philia and Eros. Philia is the serene love of those who have shared their existence for twenty years. Eros is passion with all that that implies in terms of bliss and suffering and it is this passion one aims to arouse with a love potion. Indeed, it is worth noting that, in Donizetti’s opera, the creator of the elixir is called Dulcamara, which means bitter-sweet.

Do you really think one can arouse romantic passion with a love potion?

Tobie Nathan: The idea might seem contentious to some, over-the-top even, but the fact remains that it has haunted our culture since Antiquity. The Greeks had an expression to refer to any object used to manipulate someone: they spoke of “objects of constraint”. If you find it ridiculous that an object could be used to control someone, consider the telephone you have placed on the table: there’s an object you keep permanently with you, which links you to another person – to a multitude of people in fact! – and which constrains you to carry out numerous actions. It’s an object of constraint.

When did these ‘objects of constraint’ first appear?

Tobie Nathan: We have found evidence of these famous objects, often ceramics, dating back to Antiquity. The Greeks, whom one imagines as being fascinated by rationality, believed strongly in this kind of manipulation: there were numerous cases of trials in which people claimed to be victims of one of these objects. Some of those accused even went to prison. The Greeks had doubtless borrowed the idea from the Mesopotamians who had in turn taken it from the Egyptians. One should add that these are “techniques” and techniques are what flow most naturally from one culture to the other. In the Middle Ages, such objects enjoyed huge popularity. In the 12th century, a certain Albertus Magnus wrote an official treaty on magic spells which has survived until our times: it’s the sort of book you can still pick up from the second-hand book sellers on the banks of the Seine. It contains a celebrated recipe for making anyone you choose fall passionately in love with you…

This form of message is in every way comparable to the love potion except for the fact that it directs desire not to a human being but to a material object.

The moment has come to ask you for the recipe for one of these famous potions…

Tobie Nathan: Yes, of course. Do you know what a “love-apple” is, not the sort you eat at the funfair, but the real apple of love according to Albertus Magnus, the one that will make absolutely anybody fall in love with you? Take an apple, cut it in half and scoop out the core. Take three hairs from the head of your beloved and plait them together with three hairs from your own head and place the plait in the centre of the apple. Add a slip of paper bearing your own name and that of your beloved, written in your blood. Address your prayer to Sheva – doubtless a corruption of the Hebrew name Bathsheba! – close the two halves of the apple and bake it in the oven. All that remains is to activate the spell with myrrh and place the baked apple under your beloved’s bed. During the night, the apple will release its essence and in three days the person will fall madly in love with you: Albertus Magnus is quite categorical.

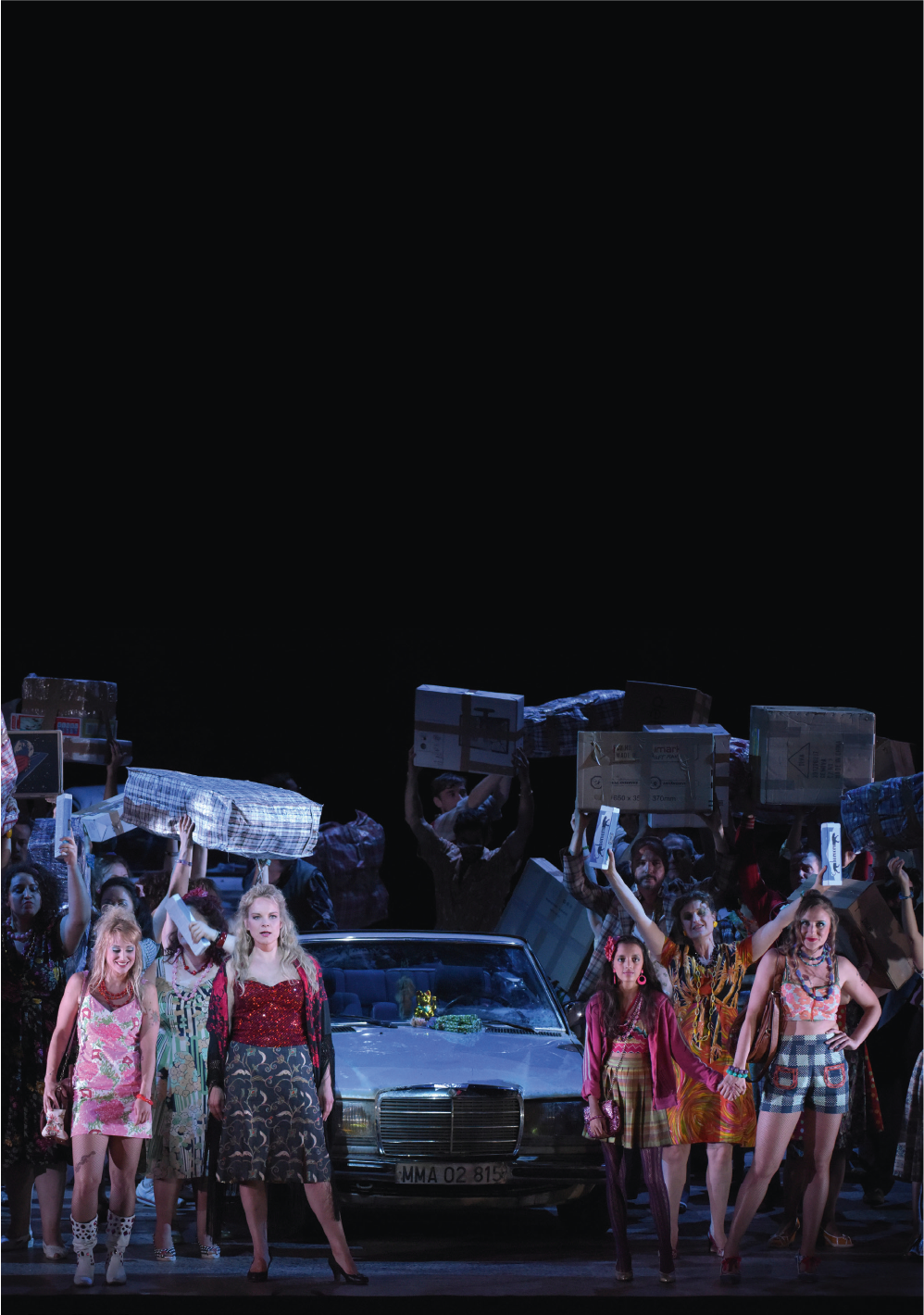

In The Elixir of Love, Dulcamara doesn’t bother with all those precautions…

Tobie Nathan: Maybe Donizetti’s knowledge of potions was somewhat hazy: his quotation from "Tristan and Iseult" at the beginning of the opera is very approximate! There is, however, one aspect of the question that he grasped perfectly: that of the principle of “activation”. In every culture, the object destined to arouse desire is an automat, an inert object which must be brought to life if it is to be effective. Now, how do you give life to an object? First of all, with blood of course. But not just any blood: blood that is still active: the first drops of blood to be shed and which therefore still contain life, hence the use of animal sacrifices in numerous spells… but when you don’t use blood, you can fall back on other substances: perfume, as in Le Grand’s treaty, or wine, which is a symbolically weaker version of blood. It is Bordeaux that we find in Donizetti’s opera.

When did people stop believing in love potions?

Tobie Nathan: As of the 19th Century, with the advent of mass advertising. But I wouldn’t say people stopped believing in them. It’s more that the belief was displaced, swallowed up by the consumer society. What, after all, is advertising but an attempt to create desire in consumers in the most artificial way possible? When you go to the supermarket, why do you take a fancy to one washing powder more than another? Because you’ve been exposed, or rather over exposed to advertising messages! Now, this form of message is in every way comparable to the love potion except for the fact that it directs desire not to a human being but to a material object. Advertising subverts sexual urges and redirects them towards consumer products. In this way, the societ we live in today subverts a large part of our sexual potential. In reality, we pretended we no longer believed in actively magic objects in order to develop infinitely more active forms of manipulation. Donizetti was well aware of this. His opera ends with love’s triumph, but it is Dulcamara who has the last word and for whom the happy denouement provides an unexpected advertising spot. His final words are: "Get rich!" That was the motto of the July Monarchy! Consumerism is the order of the day!

When it comes down to it, didn’t we invent love potion to satisfy a need, because we understand nothing about the nature of our desires?

Tobie Nathan: It is interesting that you refer to “the nature of desire” because there are two schools of thought on that issue: one questions what desire is and the other asks how it functions. The first, Plato, looks at desire and defines it as a feeling of longing. He is not wrong. The passion of love is above all a feeling of lacking something: even when I make love with the person I love, I yearn for them. You want to fuse with them completely but such a fusion never really takes place. One just experiences flashes of intense feeling. The psychoanalysts are on Plato’s side. Magic, on the other hand, is Aristotle’s province. Aristotle isn’t interested in the nature of love but in the way it works, in “how you do it” if you like. It’s from this second tradition that we get love potions and, as I’m sure you’ve realised, it is this tradition that I prefer.

Donizetti is in fact heir to both…

Tobie Nathan: Absolutely, because one can have two different readings of his opera. If one takes it literally and considers that Dulcamara’s love philtre works, The Elixir of Love is

Aristotelian. However, if one has a more psychological reading and takes into

account the fact that Adina’s interest in Nemorino is awakened when he shows

indifference to her, when she seems to be losing him and misses him, then it is

Platonic. Allow me to pause over the name Nemorino, which signifies “nobody”:

it is through love that he becomes someone, that he becomes himself.

To the fundamental question “Who am I?”, The other person then intervenes by giving me the answer, “You are the one who loves me.”

Isn’t that something of a paradox, given that we are more accustomed to associate love with a loss of self?

In literature perhaps, but not in philosophy. As I am incapable of defining myself on my own, I have to define myself by the links that bind me to other people. To the fundamental question “Who am I?” philosophy provided an answer very early on using objects, in the psychoanalytical sense of the term. The scenario goes as follows: when I fall in love, I change, and this change prompts me to question who I am. The other person then intervenes by giving me the answer, “You are the one who loves me.” This is also true in social terms. We live with our parents until we encounter a love that allows us to detach ourselves from them. We then cease to be our parents’ child and become a fully-fledged social being. Love is a constituent of our autonomous beings.

In your book, you state that love is the fruit of manipulation. Aren’t you afraid that the love potion could be a golden opportunity for manipulators and other narcissistic perverts - the whole spectrum of horrors exposed by modern psychology?

Tobie Nathan: There is a fundamental difference between the love potion and the kind of manipulation practised by a narcissistic pervert. In order to dominate his victim, the pervert seeks to isolate them, cut them off from the rest of the world, from friends and family, from everything that constitutes his or her social life. A contrario, the love philtre always requires the intervention of a third party: the person who provides the potion, to be exact: Bragnae in Tristan and Iseult, Friar Lawrence in Romeo and Juliet and Dulcamara in The Elixir of Love. Through the presence of this third party, society retains a foothold in the love relationship and the couple remains firmly rooted in a social existence. In any case, when you think about it, there is always a third party in a amorous relationship.

Are you still referring to mythology or to real life?

Tobie Nathan: Real life. At least, for my part, there is always a third person in my love relationships. I remember my very first love. I must have been eleven years old. She was called Danielle and she was fourteen. One day, a girl I didn’t know came up to me and asked me: “Do you love Danielle?” I replied that I did and, from that moment on, I loved Danielle. I don’t know what was going through the mind of that little girl, but by asking her question she became the originator of my first love affair.

Propos recueillis par Simon Hatab

Tobie Nathan est professeur émérite de psychologie à l’université Paris VIII. Il est le représentant le plus connu de l’ethnopsychiatrie en France. Il est l’auteur de Philtre d’amour. Comment le rendre amoureux ? Comment la rendre amoureuse ? dans lequel il explore la thématique du philtre d’amour de l’Antiquité à nos jours, partant du principe que l’on tombe amoureux non pas au gré des rencontres, charmé par un corps harmonieux, mais parce que l’on a été l’objet d’une « capture » délibérée.