Joseph Bologne de Saint-George, known as the Chevalier de Saint-George, has all the characteristics of a character from a novel: an “inimitable” swashbuckler, a knight promoted to colonel during the French Revolution, a brilliant violinist and composer admired by his contemporaries... How could he have disappeared from history and concert halls until now?

Let’s start at the end.

On Saturday 23rd May 2020 in Martinique, statues of Victor Schœlcher were torn down from their plinths in Fort-de-France. A month later in Paris, in front of the National Assembly, the statue of Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister and author of the Code Noir of 1685, was covered in blood-red paint. Finally, on July 23rd 2020 in Basse-Terre in Guadeloupe, two days after the Saint Victor celebrations, the bust of Victor Schœlcher disappeared from the place where it had always presided.

Basse-Terre, it is there that, in 1746, Joseph Bologne de Saint-George was born to George Bologne, sugar plantation owner and to Anne Nanon, his slave. Elisabeth Jeanne Françoise Mérican, who had become George Bologne’s wife in 1739, accepted Anne Nanon and understood the love that her husband bore her. The family left Basse-Terre and arrived in Bordeaux in 1748. On her arrival, Nanon was presented as the couple’s servant and was accompanied by Joseph, just two years of age, her mother, Marguerite, and François “a mulatto aged 14 or 15”2 also a slave. At this period, the Code Noir written by Colbert was still in force in the colonies of the kingdom of France, but did not apply to those black people established in mainland France. In other words, Nanon and her son enjoyed the status of “free negroes” the moment they landed at the port of Bordeaux.

Until the French Revolution, the expression “free negro” was merely an oxymoron that testified to the pretence of liberty in the kingdom for black and mixed race people who were sometimes depreciated, sometimes fetichized by the court. Georges Bologne recognised Joseph as his legitimate son which allowed him to benefit from an education fit for the noblest aristocrat. In

May 1763, Joseph de Saint-Georges bought a commission as a squire on the decease of its previous holder, Pierre Renaut, and at 17 years of age, by royal legitimation, became a War Commander. His appointment to this office created waves and contributed to the birth of the myth surrounding the talents of the young Chevalier de Saint-George. He trained with La Boëssière, at the time the most highly reputed swordsman in the capital, and acquired the nickname “the inimitable”. His master of arms is said to have declared: “Racine created Phèdre, I created Saint-George3. A legend in his own life-time, Saint-George challenged the equally legendary fencer, the Chevalier d’Éon, to a friendly duel on the eve of the French Revolution during a stay in London.

However, during his lifetime, the Chevalier de Saint-George owed his European renown to his musical talents. As a violinist he was invited to the aristocracy's most prestigious salons and was said to be Marie-Antoinette’s music master. At the time, the Académie Royale de Musique called all the shots on the European musical scene. In Paris, it was forbidden to perform other concerts when the Academy was performing and the rules protecting its repertoire were very strict. Thus it was that the Concert Spirituel, which was to become the Salle Favart, had to pay a subscription to the Royal Academy in order to give concerts more than thirty days in the year. In Paris, a third association of musicians distinguished itself: the Concert des Amateurs. This ensemble, in which the musicians were all unpaid, was noted for specialising in contemporary compositions. In 1769, under the baton of François-Joseph Gossec, the young Chevalier de Saint-George became the lead violinist of this orchestra. In 1773 he became its conductor. The poet Pierre-Louis Moline was already proclaiming the composer’s talents in Le Mercure: “A child of taste and genius / He was born in the sacred vale /And of Terpsichore was both emulator and suckling babe. / Rivalling the God of harmony / Had he united music to poetry / he would have been taken for Apollo”4. The expression “Rivalling the God of harmony” places Saint-George in direct competition with Rameau who had died four years previously and was worshipped by generations of musicians. In 1772, the young composer sold his commission as War Commander in order to devote himself to music. It was with the Concert des Amateurs that he developed his skills in orchestration, notably in the genre of the sinfonia concertante.

The 1770s saw Saint-George at the height of his glory, his art was hailed by his contemporaries who dedicated numerous works to him in both Italy and Germany. In 1776, with the support of the Amateurs and that of Queen Marie-Antoinette, he applied for the post of director at the Académie Royale de la Musique. The course of the history of that institution might have been changed for ever that year, had Saint-George been appointed as its director, but three artists in the company opposed it with well-identified arguments. Sophie Arnoud, Rosalie Lavasseur and Marie-Madeleine Guimard, known as La Guimard, singers and dancer in the company respectively, were three artists recognised for their talent in 18th century society and who frequented the same aristocratic circles as the Chevalier. Although their correspondence indicates tension between the three artistes, they collaborated in writing a petition for the attention of the queen stipulating that “their honour and their delicacy of conscience could never permit them to take orders from a mulatto5. La Guimard, a favourite with Marie-Antoinette, was the first to sign the racist pamphlet that prevented the Chevalier from obtaining the post of director of the Académie Royale de la Musique. How could these arguments have prevailed in the face of the royal backing for Saint-George’s candidature? His rise in society and the public recognition of his talent made him an exception at that time, until the argument of his skin colour was weighed against him in the debate and disqualified him for the post. The phrase in the petition “take orders from a mulatto” thickened the glass ceiling against which the Chevalier had banged his head. The three artistes pointed the finger at both the colour of his skin and his genealogy: he was and would always be the offspring of a slave. In response to La Guimard, the Chevalier Saint-George resorted to humour and, in a few lines of verse, sketched a satirical portrait of the dancer: “If Venus were the insipid Guimard / Love would renounce her joyful graces / and, body, legs and arms, alarming the eye, / would be but an engine for beating negroes.6” As for Louis XVI, he responded to this episode by appointing nobody to the post of director of the Académie Royale de Musique. In March 1777, the king seemed however to lean towards la Guimard and her acolytes when he wrote a memorandum for the attention of the governor of Martinique in which one may read: “Free [negroes] are affranchised slaves or the descendants of affranchised slaves; however distant they may be from their origins, they forever preserve the stain of slavery and are declared ineligible for any public office. Even those gentlemen who descend in whatever degree from a woman of colour, may not enjoy the prerogatives of the nobility.7”

Although the press could make or break the reputation of an artist in a few lines of verse, this was also a period of widespread debate on societal issues and the slave trade was a prominent theme. Thanks to the Enlightenment, the second half of the 18th century saw the emergence of progressive thinking that was opposed to the Ancien Régime and fought for the abolition of slavery and a renaissance of the notion of equality for all men in the sight of the law. Its authors, sometimes behind the mask of anonymity or a pseudonym, debated the issues through articles published in periodicals such as Les Éphémérides du citoyen, which was affiliated to the Physiocrat movement. In response to a letter published in this journal on 29th September 1766 entitled “Explanation of negro slavery” which presented the slave trade as a way of saving Africans from the barbary of their kings, the following month one could read a refutation of this explanation which gave pride of place to our composer: “It is clear that negroes must be men since in Portuguese establishments they are made Christians and ordained as priests... Your author, who declares them to be totally incapable of abstract study, would be greatly surprised [...] to learn that here in Paris, even as he wrote that assertion, a negro is regarded by the artistic milieu as one of our most able musicians, not merely for his understanding or performance but for the composition of the most difficult works.”

Saint-George was held up in the public discourse as the living example of equality irrespective of skin colour. What did he think of this? Saint-George’s own stand against slavery was at the heart of his commitment to the Revolution. Although he was close to the aristocracy and the court – indeed he was put in prison on suspicion of royalism – Saint-George was to play a major role in the way the fight against the slave trade would shape the Republic after the Revolution. On 27th May 1793, the members of the 13th Regiment of the Chasseurs à cheval, a troop of black soldiers led by Saint-George during the Revolution, published an “address to the National Convention to all patriotic clubs and societies” sub-headed “For the Negroes detained in slavery in the French colonies of America under the regime of the Republic.” Among the signatories of this text are to be found the Chevalier de Saint-George and also another “mulatto”, Alexandre Dumas, father of the author of The Three Musketeers. This address was an appeal to abolish slavery in the colonies and extend the rights of man and citizen to those who were reduced to that state: “Likely, by reason, to love liberty, and to remain attached to her principles, deign, wise legislators who decreed the rights of man, deign to extend to us your benevolent gaze, no longer groaning beneath a burden too heavy for us, we will become gentle, peaceable men, we will forever broadcast the signal service you have rendered to all nature.” In the wake of this text, on 31st May and 1st and 2nd of June 1793 at the Assembly, abolitionist deputies like Julien Labuissonnière, Robespierre, and Jeanbon Saint-André debated the writing of a text to put an end to slavery in the colonies.

The authors of the address were themselves proof through their careers of the arguments they put forward for the abolition of slavery, “Are not negroes, like whites, likely to become perfected in the sciences and the arts?9”, and they anticipated a subject which, half a century later, was to be the condition on which the final abolition of slavery rested: the compensation given to slave-holders. Indeed, after 1849, 7% of state funds under the Second Republic was spent on “compensation for slave-owners” dispossessed of their slaves. Victor Schoelcher supported this compensation, for which reason, 171 years after the abolition of slavery, one may still hear, in Martinique and Guadeloupe, “Schoelcher is not our saviour”. In 2020, in a world-wide movement against racism, a few names like that of Saint-George, forgotten by history and left in the shadow of those to whom white marble and bronze have conferred immortality, re-emerge.

Like all composers of a given period, Saint-George fell into obscurity. Mozart, his contemporary and whom he would have met had Mozart not refused to play with the Concert des Amateurs in 1778 during his stay in Paris, was forgotten in the same way with the advent of the Romantics. Mozart and Saint-George had a common protector in the person of the Baron von Grimm, Saint-George’s sponsor for his application for the Académie Royale de Musique. In 1778 however, the young Austrian composer, far from being unanimously acclaimed on the Parisian stage, fell into dispute with his patron. Joseph Legros, who was director of the Concert Spirituel at the time, turned down his symphonie concertante before agreeing to perform his Paris symphony. Although he never met Saint-George, Mozart knew his work and we find several borrowings in some of his best-known works, such as Eine kleine Nacht Musik (1787) which borrows its theme from Saint-George’s Sonata no. 2 in A major for violin and piano (1770, published in 1781). On the rediscovery of the works of Saint-George, these borrowings led musicologists to call him the “Black Mozart”, a thoroughly clumsy nickname that, besides not doing justice to History, occults the identity and personality of the Chevalier, leaving only the colour of his skin.

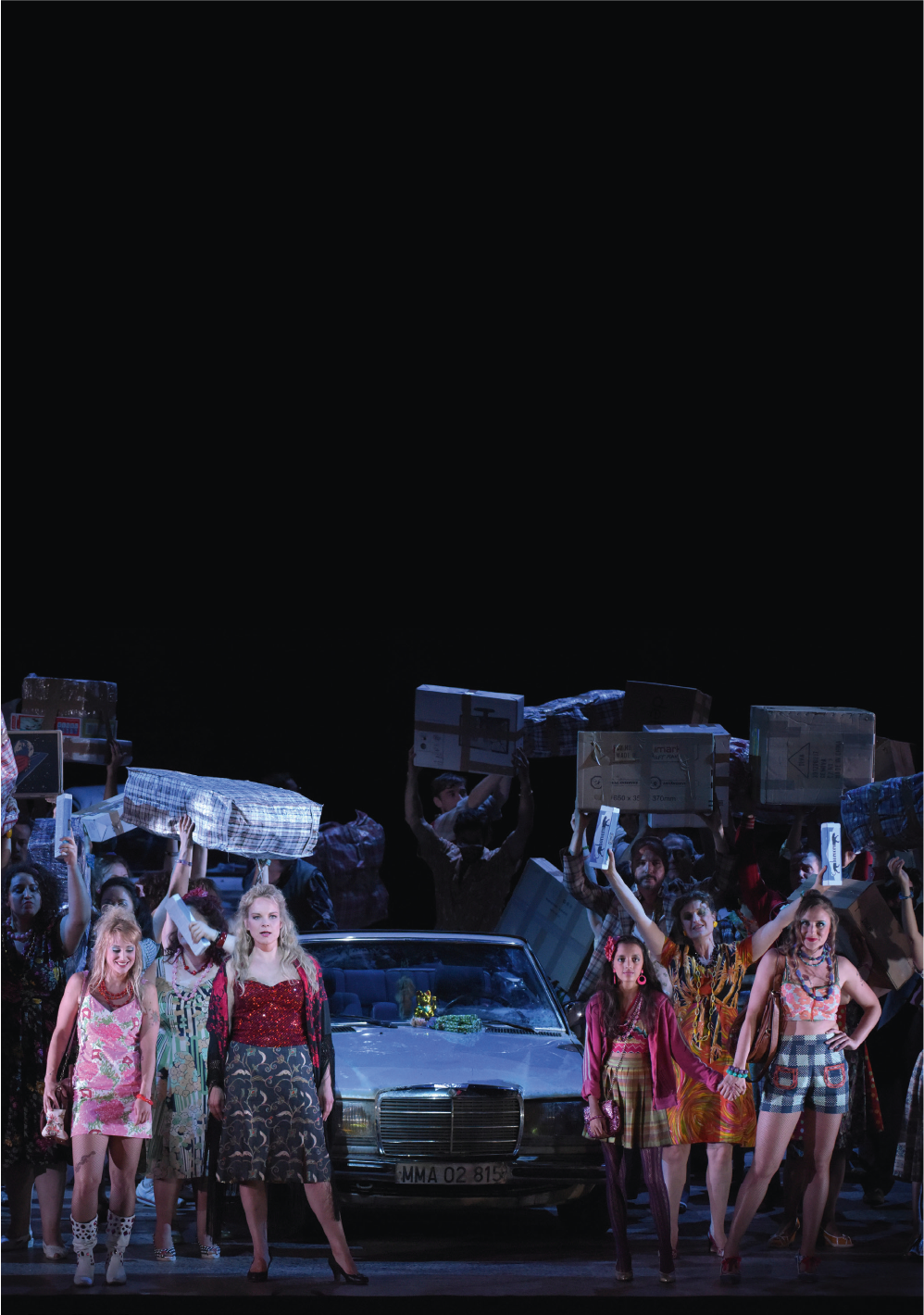

Performing Saint-George today at the Paris Opera is less an act of homage than one of recognition and justice. A major composer in his day, Saint-George was also an essential player in the building of an egalitarian Republic. “If, on this earth, tyrants find pleasure in encumbering innocent creatures with the weight of their wrath, what may console us is the hope of finding you sympathetic to our claim, and the confidence we have in your justice,10”. On 15th December last, this concert should have taken place on the stage of the Palais Garnier, whether or not it pleased Mesdames Arnoud, Levasseur and Guimard: enshrined in marble in the corridors of the Palace, they were unable to contest it. Who are the writers of History today: those enshrined in marble or those who live on through their music?