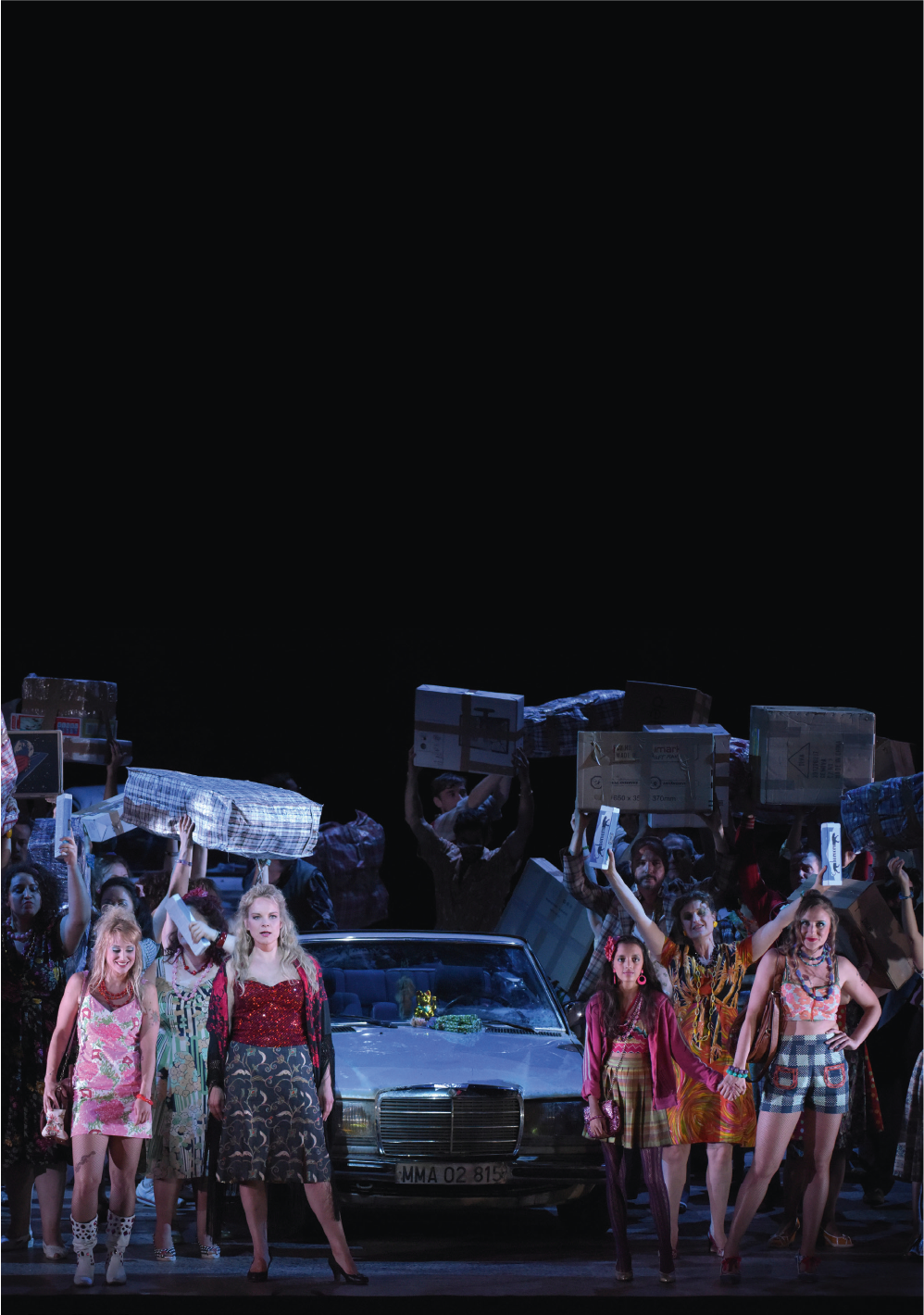

A young man by monsters finds the path to wisdom in love and friendship and, after patient initiation, confronts his fear of death with his chosen one: such is the plot for Mozart’s last opera which, depending on a person’s age, can be perceived as either a magical story or a profound metaphysical meditation. With the opera currently on the bill at the Opéra Bastille in a lugubriously beautiful production by Robert Carsen, Charlotte Ginot-Slacik explains how the characters of this initiatory tale learn to confront the limits of their existence all the better to extol its meaning.

A dual tension permeates Mozart’s last operas: on the one hand, a longing for happiness and a loving relationship as extolled in Die Entführung aus dem serail, and Le Nozze di Figaro, and which comes to fruition in Die Zauberflöte; and on the other, a reflection on death: Anxiety-ridden in Requiem, political in La Clemenza di Tito, and surmounted in Die Zauberflöte. This “hardest counterblow to utopia1” appears as the indispensable aspect of a quest for earthly happiness in which love plays the leading role. “Husband and wife and wife and husband attain divinity2”. Ernesto Napolitano has intertwined these Mozartian tales of love and death in a wonderful book3.

“As death -all being considered- is the ultimate stage of our life, I have made myself so thoroughly acquainted with this good and faithful friend of man, that not only has its image no longer anything alarming to me, but rather, something most peaceful and consolatory. And I thank my heavenly Father that he has vouchsafed to grant me the happiness and has given me the opportunity (you understand me) to learn that it is the key to our true felicity4.” So wrote Wolfgang Amadeus to his father Leopold, on April 4, 1787, almost three years after he became a Freemason. Despite those reassuring words, that “good and faithful friend of man” haunted the final works of the Viennese composer.

“Help! Help! Or I am lost, sacrificed to the cunning serpent5.” When he enters on stage, Tamino has shot all his arrows and the menacing serpent has him almost in its grasp. His staccato voice climbs into the high notes only to fade away when he faints. Saved by the entrance of the ladies, revived on the orders of the Queen of the Night, the prince, according to Mozart, is characterised above all by a faltering bravery. “You shall go to set her free, you shall be her saviour”, proclaims the coloratura Queen with tumultuous virtuosity in an imperiously compelling song that rekindles Tamino’s strength… unless she revives it through artifice. If there is a courageous creature in Die Zauberflöte, contrasting radically with the combat waged by the intermediaries of her mother the Queen of the Night, it is surely the young Pamina, who, during her first appearance and under threat from Monostatos, makes a clear reference to death: “Death does not frighten me; I only worry about my mother; she will surely die of grief”.

Courage and strength in the face of the unknown… As many themes which implicitly define the transformation towards adulthood for Tamino who is now accompanied by Pamina. The acceptance of a life-death dialectic appears as the ultimate stage of wisdom acquired at the end of a formative process or, to use Goethe’s choice of terms, a Bildung. “He who travels these laborious paths will be purified by fire, water, air and earth. If he overcomes his fear of death, he will raise himself from earth, soar heavenwards6”. For this ultimate test, announced by the armed guardians of the temple of Sarastro, Mozart makes use of a striking language comprised of tributes to Bach—a citation of a Lutheran choral—and polyphonic evocations of Catholic Masses dating back to Biber. The tone is grave and undoubtedly sacred and determines the significance of the passage. To show oneself worthy of death in order to be worthy of life… As such the Austrian composer embraces a fundamentally religious conception reoriented by the utopias of the Aufkläurung (the German Enlightenment. “Come back, come back to life! Take sacred solemnity from here with you, for only sacred solemnity can change life into eternity,”7 warned Goethe in his Wilhelm Meister (1796). The philosopher Hegel reiterates this: “The remembrance of death causes the Greeks to enjoy life, for Christians, it spoils the enjoyment of life. For them, it had the odour of life, for us the odour of death”8. Mozartian stoicism? Certainly, the composer was immersed in intellectual circles that were attentive to reinterpretations of the Classics. And yet there is no renunciation to live in Pamina and Tamino's development: their journey is a desire for happiness. Initially dominated by her mother, from whom she progressively isolates herself, the fine female character invented by Mozart is no more sensitive to Sarastro’s reason-based paternal injunctions. Rejecting the rule of silence imposed by the chorus of priests, refuting the evidence of a male initiation (“Oh Isis and Osiris! What delight! The dark night retreats from the light of the sun! Soon the noble youth will experience a new life”9, sing the priests), Pamina radically alters Tamino’s desire for light. “A woman who is not afraid of the night or death is worthy of being initiated.” The initiation of the two protagonists is part of a process of Bildung in which body and soul are indissociable. It is also a telltale mark that Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister—a literary model of Bildungsroman, an initiatory novel—is practically a contemporary of Die Zauberflöte.

“Beauty and wisdom for eternity” are the final words of Die Zauberflöte, while Pamina and Tamino appear dressed in priests’ vestments accompanied by Sarastro. Before the terror of Requiem, before the personal renouncements of Titus in La Clemenza, the opera celebrates harmony in which the fulfilment of youth overcomes all archaisms. Death, “the hardest counterblow to utopia”… Really?