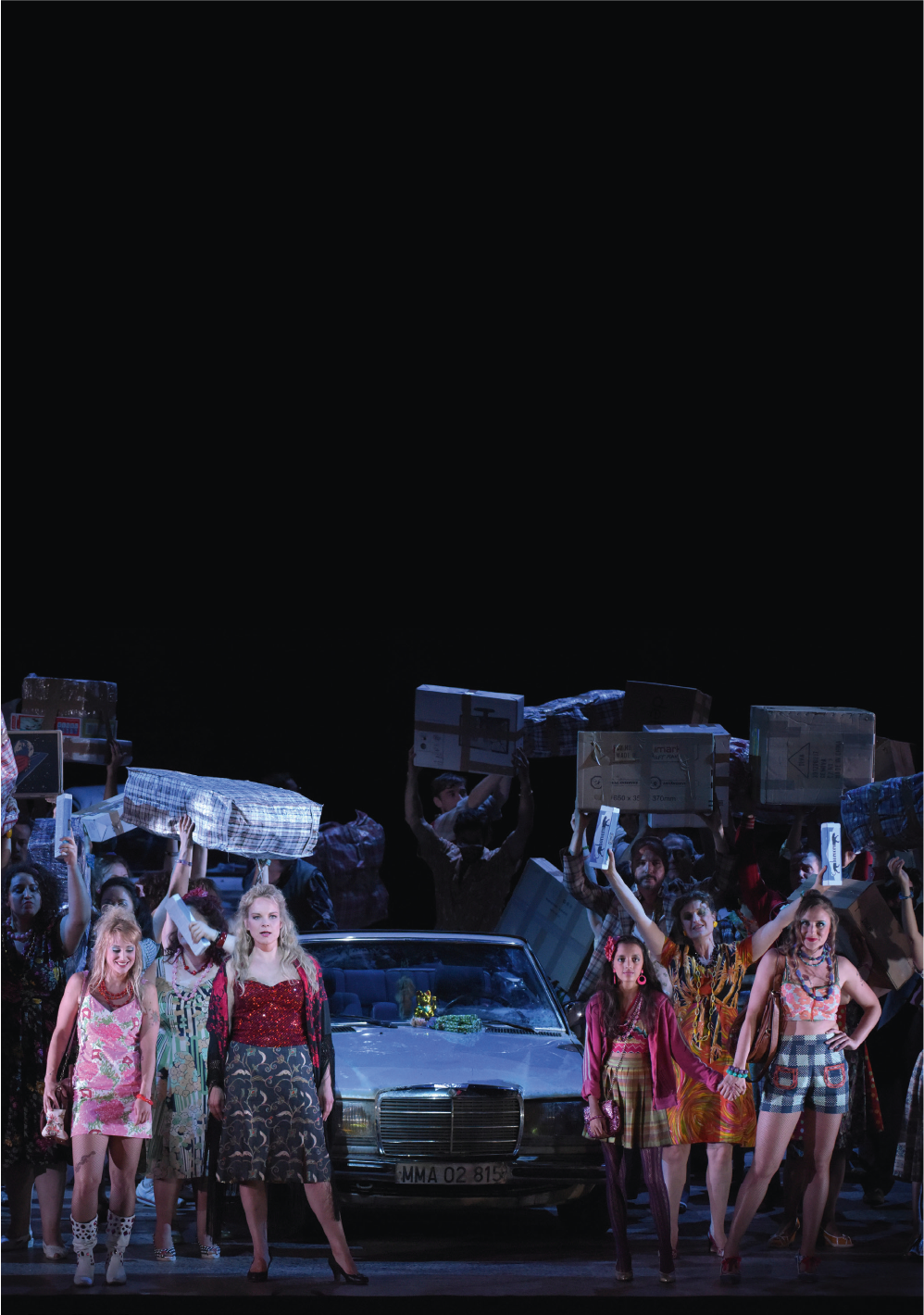

Les Troyens marks the end of a Berlioz cycle that enabled us to hear Philippe Jordan conduct La Damnation de Faust in 2015 and then Béatrice et Bénédict and Benvenuto Cellini in 2017 and 2018. The Musical Director of the Paris Opera looks back on a voyage that took us into the world of the most revolutionary of the 19th century French composers.

The programming of Les Troyens is symbolic since it was the first opera performed on the stage of the Opera Bastille, and we are currently celebrating the 30th anniversary of the theatre!

Philippe Jordan: Yes, Dmitri Tcherniakov's production is the

third at the Opéra Bastille, after the Pier Luigi Pizzi and Herbert Wernicke

productions, conducted by Myung-Whun Chung and Sylvain Cambreling. From a

musical point of view, it was important to schedule this work at the end of the

cycle, after La Damnation de Faust, Béatrice et Bénédict and Benvenuto Cellini. Les Troyens is a remarkable piece in the Berlioz catalogue. It is

his major work, his grand opera. Benvenuto

Cellini was already a large-scale work, but a comedy. Here, with this

tragic subject, Berlioz was moving closer to French grand opera in the vein of

Meyerbeer. Les Troyens reveals a

total command of his technical and aesthetic means.

Inspired by Virgil’s The Aeneid, Les Troyens recounts the epic story of Aeneas, the Trojan prince and legendary founder of Italy. Could you tell us a little about Berlioz’s quest for an ancient ideal?

Ph.J.: From one work to another, I am struck by

Berlioz’s fidelity to a flamboyant style, combined with a desire to create a

unique world for each subject. For La

Damnation de Faust, based on the

work by Goethe, he turned to a German style influenced by Weber and his Freischütz, Schumann and Mendelssohn, as

the student songs suggest. In Benvenuto

Cellini, which refers to Italian history, one hears a great deal of Rossini

and a touch of Bellini and Donizetti as well. Béatrice et Bénédict, which also evokes Italy, subtly reflects

southern atmospheres. With Les Troyens,

he sets out in search of an ancient style. However, at the time, very little

was known about that style. So, Berlioz went ahead and invented and created a

sound. Aware that in Ancient times there were no stringed instruments played

with bows, he used woodwind, brass, kettledrums and ancient flutes ( today

replaced by oboes)—particularly in the first choral— in which the people of

Troy express their joy—in order to obtain a strange and archaic sound. Aside

from the arrival of Cassandra, supported by an entrance of strings that lends a

sudden sense of tragedy, and aside from a few pizzicati on the cello and the

viola, the strings are conspicuously absent.

This taste for antiquity reminds us of his passion for Gluck’s music which was a staple during his youth…

Ph.J.: Indeed, his search for an ancient aesthetic led

him to borrow from Gluck, one of the composers who, with his

mythologically-based operatic tragedies, worked the hardest to revive that

musical past. Berlioz treated the voice in the same way as the German master

and composed accompanying recitatives whose prosody resembled that of Alceste. The principal female roles in Les Troyens were not written for

sopranos. Here again, the aim was to approach Gluck’s style which favoured

deeper voices. With the latter, the great heroines were mezzos, which would

also be the case with Berlioz.

What are the vocal requirements of the work’s principal roles?

Ph.J.: Cassandra is a role with some beautiful high

notes, however its interpretation requires an extremely good medium. Compared

to Dido, the role is more theatrical and requires a singer who is also a

proficient actress. It’s more recitative and more expressive. With Dido, who

sings all the great lyrical phrases, beauty comes before expression. Aeneas,

like the great male roles with Meyerbeer, or Rossini with Guillaume Tell,

requires a heroic tenor who can sing opera with extraordinary high notes and a

vocal flexibility which few performers possess. The chorus for its part, plays

a major role, as is always the case with grand opera. In the first part,

Berlioz exploits it for dramatic effect magnificently: it personifies Troy and

its people. It remains active in Carthage, but it is more in the background and

thus becomes more a commentator. And this works to highlight Dido and Aeneas

the principal characters.

The influence of Gluck is evident in Les Troyens, but there was another composer who was also important for Berlioz, if not more so, and that is Beethoven. Could you tell us a little about what he brought to the art of the French composer?

Ph.J.: Beethoven’s influence over the young Berlioz

was major. The obvious relationship between the Symphonie fantastique and the Pastorale

attests to this. They share the presence of sung parts, the same key and a

similar orchestration. While owing a great deal to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Berlioz’s operatic work

is also influenced by Fidelio. Later,

after his contact with Italy, his composition would further evolve. The

discovery of Italian opera and the history and artistic heritage of transalpine

culture in general would lead him along new stylistic paths.

You mentioned the orchestration. Berlioz himself was the author of a treatise on instrumentation and orchestration...

Ph.J.: Clearly, Berlioz is all about orchestration! In

Les Troyens, each number has its own

sound thanks to a remarkable work of orchestration. He develops colours of

great finesse. But here, his musical expertise goes beyond the mere field of

orchestration. The treatment of the melodies also contributes greatly to the

uniformity and general harmony that characterises the work.

Berlioz was a composer, a theorist, a critic, and also a dramatist. What can we learn from him about the relationship between text and music?

Ph.J.: Yes, Berlioz was not just a great composer, he

was also a great author who, like Wagner, wrote his own librettos. It is not an

exaggeration to say that both men were musical geniuses and genuine poets. They

were artists who were open to all the arts. The literary quality of their works

can be discussed, yet one has to recognise the real synergy that exists between

their texts and their music. Berlioz, again like Wagner, sought totality in

art. He was a great visionary who wanted to develop original forms. Already,

with his Symphonie fantastique, that

wish was expressed in his desire to compose a symphonic poem, to discover new

compositional avenues along the lines of those initiated by Beethoven with his Ninth Symphony, in terms of

orchestration and the use of text and chorus.

There is an emblematic figure of 19th century music who forms a link between Berlioz and Wagner. And that is Franz Liszt who helped to promote the art of the French composer and have his music played…

Ph.J.: The back and forth between all those artists

was systematic and fruitful. They shared the ambition to revolutionise their

art and compose the music of the 19th century. Berlioz’s

contribution to the field of symphonic music is considerable. Without the Symphonie Fantastique, the music of

Wagner, the symphonic poems of Liszt, and later, those of Richard Strauss would

not have been what they are. Strauss also complemented Berlioz’s Treatise on Instrumentation, which he

was especially familiar with. I hear a lot of Berlioz in his Don Quixote. Not only from the point of

view of the means used to give form to a musical idea taken from a subject, but

also in the orchestration. Certain flourishes of Strauss’s symphonic poem are

highly reminiscent of Les Troyens. It

is also interesting to note that Wagner’s Tristan

und Isolde and Les Troyens were

composed at the same time. In the treatment of the voices, the orchestration

and the harmony of G Flat Major, the duet between Dido and Aeneas is noticeably

evocative of O sink hernieder Nacht der

Liebe, the love duet in the second act of “Tristan”, which nevertheless uses more modulation. So, all these masters were fascinated by, understood

by, and sometimes criticised by each other. However, we cannot deny the

reciprocal influences they exerted on each another. Without their encounters,

music would never have been able to evolve. Battles are never won alone!